By Sondra Ford

Editor’s note: a big thank you to IFF and our community partners for their review and input on this piece.

Even with the best intentions, disinvested communities–most especially communities of color–may be harmed by commonplace procedures established by institutions like banks and municipalities. Often, this is because these procedures are created to benefit institutions and not the communities that need assistance.

This is not a new reality. Nationwide, history is full of examples of stories of targeted, intentional assault on neighborhoods created by structural racism. The most well-known of them include:

Redlining: Beginning in the 1950s the determination of what communities would be eligible for federal funding for the purchase of homes, including Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veterans Affairs (VA) loans and guarantees, purposely excluded Black communities. Maps were drawn that literally included red lines around the neighborhoods that were to be excluded from eligibility for federal funding. Redlining is a widely known example of a government-sponsored program specifically designed to ensure that financing and other opportunities provided to white neighborhoods were not afforded to Black communities.

Blockbusting/White Flight: In the 50s, before the height of the civil rights movement, realtors (and others) illegally encouraged homeowners, generally in white neighborhoods, to sell at below-market prices. One of the mechanisms used to promote and convince the residents to sell was the “fear” of Black people moving into their neighborhoods. As homes were sold by white homeowners at reduced prices, Black families that purchased these homes paid above market prices. To afford the homes, Black homeowners often housed extended family members or others for additional income. Additionally, neighborhood services were reduced. The neighborhood disinvestment and the overuse of homes along with other negative issues created a vicious cycle that caused the homes and neighborhoods to deteriorate.

Building highways through Black communities: In the 50s and 60s, because of the Federal Highway Act of 1956, many Black neighborhoods saw their communities split to make way for the new national interstate system. Frequently referred to as urban renewal, federal funds were used to remove people and businesses from neighborhoods that had been historically thriving and predominantly Black. Running highways through neighborhoods reduced city services, created new traffic issues, and increased pollution from vehicle exhausts. The government’s ability to do this was a product of redlining and blockbusting.

These assaults on Black neighborhoods imposed by the government and White dominant systems are well-documented. The residual effects of these activities can be clearly seen in many neighborhoods today and continue to have residual effects on neighborhoods and property values. Here, we will explore some of these negative effects and propose solutions.

Redlining v2.0

Appraisals

When someone purchases a home using the proceeds of a mortgage, the financial institution will base the amount of money they deem you eligible to borrow on several things. Some of these criteria, such as down payment and credit score, are under your control, or at least you can go into the process knowing what those numbers look like. But what about the appraisal?

Appraisals base the value of real estate on several factors related to the size, condition, use, and perhaps most importantly, location. Size and use can be fairly objective. The location, however, provides an opportunity for appraisers to subjectively assess value based on comparable data. That comparable data is typically similar buildings set in similar locations. Similar evaluation tools are used for the purchase of commercial properties.

Imagine an example of a building set in a neighborhood that had been redlined, divided by a freeway, or both. That neighborhood will have suffered from decades of disinvestment, nearby vacant buildings, and vacant land which are direct results of systemic racism. Government-sanctioned, private-encouraged, and White-endorsed racism in the built environment created the conditions of these neighborhoods. And therefore, the property has an appraised value which has the effect of qualifying the potential buyer for a smaller loan.

This same building in a neighborhood boasting investment in the neighborhood infrastructure, unburdened by a history of redlining will garner a higher appraised value. The mathematics of the two development projects can be found in the IFF article, The Appraisal Bias: How more equitable underwriting can increase capital in communities of color.

Solution:

Eliminate appraisals as prerequisites for loan funds in disinvested areas. The data is clear that racial bias exists; so much so that the Biden Administration has recently created a task force to address this bias. CDFIs can get ahead of this by removing the appraisal requirement in communities of color.

RDA: Redevelopment Agreements

Tax delinquent and abandoned properties may be taken over by the municipality in which they are domiciled. These buildings/lots are typically abandoned as a remnant of a larger neighborhood abandonment or disinvestment. To get these properties back on tax rolls or rehabbed to become potential catalysts for additional development, the municipality may agree to sell the property for as little as $1. In exchange for the “free” property, the municipality may require that the new owner execute an agreement that might limit things like how the property can be used or who it can be sold to. The agreement is referred to as a Redevelopment Agreement (RDA).

The City of Chicago typically executes this type of agreement for properties that it transfers for significantly lower-than-market-value to acquiring entities. These properties are typically in disinvested neighborhoods that the city has indicated are priority redevelopment areas: areas that may have been redlined. SPARCC recently financed one such project with a partner in a Chicago neighborhood.

RDAs, while great in theory, have unintended consequences that can prevent development from occurring or seriously hamper it. Because RDA properties are in disinvested neighborhoods, the appraisal price comes in lower than it would if it was in another neighborhood–so the developer/property buyer is already at a disadvantage. Appraisers are likely to lower the value of a property further if it is subject to an RDA. That is because RDA properties have added requirements that comparable properties without RDAs are not subject to. RDA requirements might include:

- Requiring owner to use the property for specific purposes related to its current business

- Requiring any successor organization to use it for non-profit purposes

- Deescalating % of net sales proceed must be paid to city

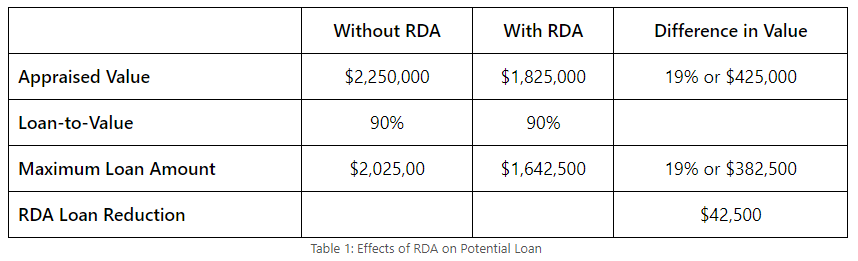

A further lowering of the property value creates an additional financing gap for the developer. The community organization acquired a building from the city to rehabilitate as a for community use. Two appraisals were done for this project with the only difference being adjustments for the RDA, reducing the value by almost 20%. Development costs don’t change as a result of appraised values. In fact, delays in the closing process caused by the need to identify additional funding could increase development costs. Underwriting of capital stacks is carefully calculated to ensure that the project can manage debt and other building expenses over time. The typical RDA project may not have the revenue needed to service additional debt, making the need to identify additional low-cost funds necessary. Absent additional funds, the project must be downsized (which incurs its own costs) or may never even break ground.

Assuming a maximum loan to value of 90%, the reduced loan amount resulting from the adjustment made to an appraisal due to the restrictions in the RDA are shown in Table 1 below.

Solutions:

- Eliminate or modify appraisal requirement

- Eliminate or modify RDA requirement

- Work with appraisers to reduce/remove the effect RDAs have on the value

- Municipalities (or philanthropy, or other source) fill the capital gap created by the RDA reduction in value with no- or low-cost capital

Disparate treatment of property values, investment, and rules carry consequences for communities. Whether the issues relate to a history of structural racism or municipalities burdening disinvested communities with requirements that make redevelopment more difficult, harmful practices must be highlighted and corrected.

To the credit of the Biden-Harris Administration, they have taken on the issue of bias in appraisals through the Property Appraisal and Valuation Equity (PAVE) Action Plan.