By James Yelen

Just what exactly is “community ownership”? Depending on who you ask, the answer may differ, with some emphasizing how an asset or entity is controlled through decision-making and governance structures, others focusing on the proposed goal or benefit (such as permanent affordability), and still others interested in the degree to which community members or residents are able to take an ownership stake and capture a share of economic value that is created. Even the term itself has evaded consensus — frameworks such as community wealth building, community stewardship the solidarity economy, shared equity (in the homeownership context), alternative ownership, Ujima, and others are often used to describe an overlapping set of development models and approaches. But one common thread is a recognition that unequal access to capital and growing wealth inequality–particularly the racial wealth gap–cannot be addressed by “traditional” forms of asset ownership alone. Furthermore, there’s an acknowledgement that exclusion and extraction are built into our current economic systems and models of development finance. The shortcomings of these systems can mean additional consequences for climate vulnerability and the physical and mental health of community members, with some leaders in this space urging a transition to more restorative practices that confront these harms through new investment practices. In other words, community ownership is a principle or ideal state, and the “how” might differ depending on a specific community’s context, needs, and history. Community ownership has become a crosscutting theme in our SPARCC work, pursued by local leaders across the six sites and elevated through curated resources, webinars and events. We have come to realize that for these models to prosper, the community development field cannot take a narrow approach to supporting them — we must focus on resourcing and aligning our entire ecosystem.

The Case for Community Ownership

Throughout SPARCC, we have tried to maintain an expansive definition of community ownership models that captures the diverse strategies pursued by our on-the-ground partners. As we have previously written, “community ownership envisions opening the ownership of homes, commercial property, and backyard cottages to the people who have built and who maintain the culture of the community. It also opens a pathway for low-income and people of color to local control of community assets.” This could mean limited equity housing cooperatives in the affordable housing space, worker-owned cooperatives as a way to organize a business, community land trusts as a means of locally-driven land stewardship, or community-based investment vehicles to finance mission-driven development. Much has been written about the nuances, benefits, challenges and impact of these models, but to keep things simple we’ll highlight three key ingredients of community ownership that we have observed through SPARCC:

- Inclusive governance models that ensure decision-making is driven by the most impacted community members and designed with an eye toward democratic representation. Maintaining and strengthening our civic infrastructure is more important now than ever; community ownership models provide laboratories for cooperation, building consensus, and harnessing inter-dependence. While the level of participation will range based on the time, preferences, and capacity of those involved, opportunities to exercise self-determination are essential.

- Shared economic benefits that balance financial sustainability, wealth-building opportunities for participants, and the interests of the broader community. In an era of ever-expanding wealth inequality and financial speculation, we need models that give residents and workers an opportunity to experience direct economic gains and intergenerational asset ownership.

- Local and place-based focus that recirculates wealth within the community, builds neighborhood resources, and deters absentee ownership. Orienting toward local institutions, networks, and assets helps build on existing strengths and culture, increases economic resilience to external shocks, encourages more environmentally sustainable practices, and contributes to a multiplier effect as tax dollars, sales revenue, and job creation stay within the community.

Beyond Organizational Capacity

Despite its promise and growing track record, community ownership has historically lived on the margins of community development and economic policy. Our current community development financial system, public funding programs, and tried solutions to the persistence of inequality and racial injustice continue to reflect this. Recently, community ownership models have been explored and championed by more mainstream think tanks, foundations, and intermediaries, including the Urban Institute, Brookings Institution, and LISC, among others. Increasingly, these actors — SPARCC intermediaries included — are coming to realize that if we want these models to “scale up,” we cannot expect our current systems to provide that opportunity on their own.

Funders and others in positions of power tend to look at the relatively tiny fraction of the economy that community ownership models represent and question their potential, often pointing to the capacity of implementing organizations as a limitation. But while important, organizational capacity alone is not enough, and it doesn’t grow in a vacuum — there needs to be a suitable enabling environment or ecosystem with all of the elements that support growth.

In the ecological context, ecosystems refer to the living and non-living components of a natural setting (e.g., a prairie or savanna) that interact with one another to sustain life amidst changing conditions and resources. But increasingly, analysts have found the ecosystem to be a powerful metaphor for understanding the functioning of social systems, a trend that has especially caught on in the corporate world. For community development work, this includes legal frameworks, public policy, financing, technical assistance offerings, social networks, and cultural norms that contribute to the success and failures of different models.

We can take a look at the world of affordable housing for an example. Since its introduction to the U.S. tax code in 1986, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit has been the largest source of federal subsidy for the construction of homes affordable to low-income families and individuals. Consequently, over the last several decades, the evolution in the practices and priorities of financial institutions, developers, public agencies and other actors have centered on the tax-credit model. This has led to the production and preservation of over 3 million units of affordable, predominantly rental, housing, representing a major component of our social safety net for millions of low-income people across the country. It has also meant that housing models that do not mesh as well with tax credit financing — such as limited equity housing cooperatives and community land trusts — are at a disadvantage when competing for scarce public resources since they have a harder time “leveraging” tax credits. They are also less likely to be prioritized in the creation of new capital products, face an uphill battle when seeking well-aligned support services like property management, and frequently do not see their priorities reflected in the agendas of larger players in the public policy realm.

Even the strongest organizations will fail to reach their full potential when forced to navigate regulations or accept project financing that does not account for the unique aspects of their model. Similarly, gaining public and philanthropic support is more challenging when decisionmakers are unfamiliar with the models in question or have ingrained biases against shared ownership and governance structures. In a world that is built around binary models of ownership and control over resources and enterprise (e.g., employer/employee, landlord/renter, lender/borrower, etc.) creating a strong ecosystem for community ownership does not just happen on its own — it takes intentional strategy, active partnerships, and grassroots organizing at the local level.

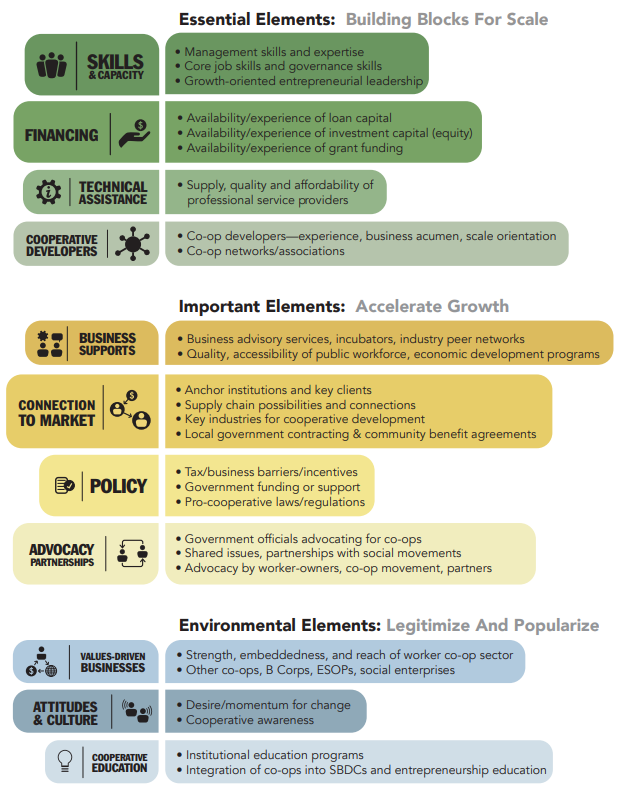

Organizations like Project Equity and the Democracy at Work Institute have provided a helpful ecosystem framing in the context of worker-owned cooperatives. “The ecosystem,” they explain, “includes actors — individuals, organizations and institutions — and elements that interact to support or inhibit scaled growth.” They look at the stages of ecosystem development and identify three broad categories that each have their own subcomponents, as shown in the graphic below.

What is crucial about this framework is how it focuses on the full lifecycle of organizational development, interlocking and complementary external factors such as policy, partnerships, and technical assistance, as well more diffuse elements like attitudes and values that can be impacted by education and organizing. This type of framing can and should be applied across other domains of community ownership. Fortunately, we have started to see examples of initiatives that embody this approach, perhaps most importantly through public funding programs that stimulate organizational growth and encourage other institutions to play a role. A couple of recent examples include:

- California’s Foreclosure Intervention Housing Preservation Program (FIHPP) which will invest $500 million into the preservation of residential properties between one and 25 units that show signs of financial and physical distress. With significant input from the California Community Land Trust Network, Enterprise Community Partners, Housing California, and other state and local advocacy groups, FIHPP will include funding for robust technical assistance, generous and flexible project financing, and provide pathways for smaller mission-aligned organizations that lack traditional real estate experience to grow their capacity and become eligible to use FIHPP funds. While the program is still being developed, California’s Department of Housing and Community Development has been intentional in its program design process to make sure that FIHPP works in harmony with shared ownership models like land trusts and co-ops and has made it a priority to build the long-term sustainability of participating organizations. Notably, FIHPP’s funding will be administered by third party community development financial institutions (CDFIs) selected on a competitive basis, and they will be required to adapt their practices and capital offerings to the flexibility demanded by the program guidelines. The coalition that has fought for the creation of FIHPP — which includes several organizations from the Bay Area SPARCC table Bay Area for All — knows that the program is just part of a bigger picture pursuit of housing justice. They continue to fight for complementary policy, like statewide “Right of First Offer” legislation, and additional budget allocations for project funding and technical assistance.

- In Chicago, the City’s 2021 launch of a $15 million Community Wealth Building Pilot similarly illustrates comprehensive thinking about how to support community ownership models. While the pilot will soon offer significant funding for direct project-related costs — the first time the City has done this specifically for community ownership work — it will first invest in the ecosystem itself through extensive relationship-building and multi-year grants and contracts for technical assistance providers with a diverse range of expertise. City staff began the program design process by partnering with leaders from across Chicago’s economic development sector through a CWB Advisory Council, leaning on local knowledge and a spirit of collaboration to better understand the landscape, daylight areas where support is most needed, and identify opportunities (such as philanthropic funding) that can complement the City’s efforts. Drawing in part from Chicago’s allocation of American Recovery Plan Act dollars, the CWB Pilot also represents an example of how flexible federal funding, when motivated by grassroots advocacy and critical public sector leadership, can be used in holistic ways that go beyond the status quo.

In addition to these recent public sector programs, national organizations like The Democracy Collaborative (TDC) have championed a broad-based vision of economic democracy through initiatives such as the Next System Project, which mixes research, popular education materials and communications strategies to increase awareness of the transformative potential of community ownership. TDC was an early partner in Chicago’s pilot initiative and is currently working with other localities on how to expand support for local community ownership work being led by grassroots organizations. These examples illustrate how to think more holistically about supporting projects that exhibit the qualities of community ownership, something our local SPARCC partners have been urging us to do for the last few years.

When taken together, the message is clear: for community ownership models to have a fair shot at success and long-term sustainability, we need buy-in, active support, and coordinated action from leaders across the community development field, including our public sector, philanthropic, and lending institutions. At an organizational level, that means listening to on-the-ground community ownership practitioners to identify how their needs align with your strengths, and then designing and implementing initiatives that are calibrated specifically to those needs. For a city, that may look like a full-spectrum approach like Chicago’s CWB pilot; for a CDFI, that might look more like the California Community-Owned Real Estate Program (CalCORE), a technical assistance and capacity-building program launched by Community Vision and Genesis LA in 2021. At SPARCC, we have focused on capital grants to innovative community ownership projects like The Guild’s Groundcover in Atlanta and East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative in the San Francisco Bay Area, and several community land trusts; research, communications and education work; and most recently, facilitating a peer learning space for BIPOC-led and community-based organizations.

At a higher level, regional and national institutions need to coordinate more closely to align their immense resources in complementary ways, rather than supporting these models intermittently and in isolation. That means CDFIs and impact investors collaborating and sharing notes on capital offerings, policy organizations entering into new coalitions and listening more closely to grassroots advocates that have championed these models for years, and philanthropy using its convening and grantmaking abilities to encourage experimentation and guide private capital and new federal spending towards community ownership. This is how we ensure that our individual contributions are addressing the structural barriers to scaling up the work of our community-based partners; this is how we build a stronger community ownership ecosystem.